“We’re gathered round a fire

and it’s the autumn of the year.

We’re at the southern edge

of the northern hemisphere.”

So begins the fifth song from the new Nights of Grief and Mystery record. ‘Records’, actually. We’re pressing vinyl this time, two discs worth. More about that in the coming months.

But now I’m down south again, further south than usual this time. Tropically south this time, is how it worked out. I had a kind of extreme invitation: a stand and deliver session in spontaneous translation in an equator-adjacent place I’d never been, never been close to. “People here know your work”, I was told.

In this trade, ‘people’ can mean four people, all friends of the erstwhile organizer. Event excitement can distort the sense of what’s possible, until limits are bad vibes and likelihoods are foreclosing defeats. And I am a northern hemisphere kind of act, truth be told. I’m just not relaxed or exotic enough to rouse cool running kinds of vibes. On top of all that, my recent health adventures have winnowed away my ability to hang, resulting in a kind of tilted, internally strained kind of subtle perpetual motion, disqualifying me from the appearance of coolness. I think I’m always looking as though I’m waiting for something to happen that hasn’t happened yet. ‘Northern’, in other words.

A last minute pop-up radio interview emerged on the Friday, meant mainly for the expats in the listening area. I hadn’t done an ‘in-studio’ thing in years. These can strain listening etiquette to the breaking point, the interviewer sitting on the opposite end of a yards-long table, headphones, cables, microphones, engineers, producers and a relentless set of questions that go relentlessly on towards their own argumentative goal and purpose, regardless of what I might have just said, regardless of the weather of the subject matter. The host had her mother in the studio with her. Unusual. But I took it as a sign that she was likely to behave.

And she did, as it turned out. She was keen and kind and almost kindred, and her questions were genuine and well made. The hour went breezily by. I hit my stride, found my groove, impressed mom, and stepped back out into the tropical heat thinking that maybe it would add a few people to the audience for tomorrow’s gig.

Gig day arrived, and we were headlong into the snarl of early traffic, heading out into the campo. It was the first event at the patron’s country home. Heading down the long entrance road, things got unexpected, layered. The venue was, it turned out, the big house of an aged, jungle shrouded hacienda, a remnant, reminiscent of the truly grim old days of encomienda. The rooms were two stories high, tiled, faded. Easy to disown. Easy to make distance from, discredit. Easy for once for a northerner to be on the right side of history.

Anything that’s real is not that simple, usually. The vibes were like omens: complex, challenging to read. The new owners were good people. That was clear. Their Mayan neighbours were born there, had fond childhood memories of it, and without owning it still considered it a part of their cultural patrimony. They were in on the organizing of the event. A good number of them came to hear from the northern stranger. I hovered in the green room, made a few chi gong tension release moves in vain, wondered where to aim.

The talk went very well, thanks in part to the acrobatic spontaneous translation of my audio Spanish doppleganger at the back, in part to the generous and sincere questions of our host, and to the beautiful attention afforded me by those who came all that way to listen. There was an amiable and aroused line of people who wanted a word when I was done. After, to dispel the post-gig mojo wind up, I was taken for a walk around the hacienda. It had loads of outbuildings, drained reservoirs, trees coming up through concrete floors. It had its own church, padlocked and dank and echoing with the mixed spirit ancestry of the land as my wife sang an old hymn through the broken shutters.

Scattered around the place: the shells of factories that up to maybe a hundred years ago processed sisal. This place was in on what was once a world monopoly on the manufacture of rope. Green gold, they called it. The city I woke up in is thick with nineteenth century mansions funded by that monopoly, scores and scores of them. Those must have been heady, opulent, tormented times, until, so I’m told, the Chinese invented plastic rope and in a growing season or two gutted the sisal market for good, and gave the hacienda back to the jungle.

*My farm was a barn-bereft affair when I bought it a quarter century ago. The poor soil was poor enough, the reliance on the monsanto green revolution grim enough, the fallen fences failed enough. But an eastern Ontario farm without a barn is a cursory, stringent affair. I had barn envy for the best part of two decades, without the funds to soothe it.

Then, two strokes of fortune: Die Wise found its audience. The Orphan Wisdom School found its groove. With them I built a teaching hall. Years down the road I heard that the farm across the river was to be severed – a rough, serrated word – and the buildings razed. I found the man contracted to do the razing, sounded him out about dismantling and rebuilding some portion of the massive barn complex on my place. “Can do”, he said. “Go see which part you want.”

Though I don’t know horses at all, I’m guessing that choosing which part of a barn to save is like choosing from among old horses. You look in the mouth, though for what I don’t know. You look at the feet for imbalance and wear. And you look down the length of the back, for sway, for seizure, for sag. I stood fifty yards back, tried to get the excitement out of my bones long enough to see what I was looking at, ran my eye over the old sequence of buildings as if it were my hand, to cypher which might survive the dislocation and serve my place.

The place had seen better days. Every day was better for it than these ones. The end buildings, the younger ones, were skewed from their hastily set foundations. The roofs had failed badly over the decades. But there was a portion in the middle, maybe forty feet long. Depending on what was inside, it might work.

I forced open a livestock gate, made my way in. There was only gray, dusty light to go by, dank shadows. It had been picked over, very little in the way of agrarian treasure there. The bones looked good, though. There was a second story, but no stair or ladder to get up. I found a hole in the floorboards wide enough to allow me, eased myself awkwardly through. I waited for my eyes to pick out shape.

What loomed was a kind of silvery mountain. At first, that’s what the entire second story was: a swarthy, silvery mountain. We counted them later: almost five hundred old hay bales, bleached the colour of desert bone.

*A farm’s treasure is in the facts of the land. And the facts of the land are stored up sometimes, when you’re spared somehow, when the vagaries of weather and pestilence and any kind of luck at all allow. And so much of the seeming debris of the place is actually a visitation of lacrimae rerum, the tears that are in all things. Every fieldstone hoisted up to make a separation of fields, every dry pit that was once a watering reservoir, every squared timber outbuilding leaking spring meltwater has human labour running all the way through it, purposeful and determined and hopeful and deferred, or defiled, or defeated.

An old barn is all of those things. This is no less true when you save it from the wrecker, the vandal, the homeless nostalgic. You can even save it from time and time’s disassembling minions, for a while. Depending upon where in the cycle of tumblings down you might appear, you can see all of this human and more-than-human striving and forestalling coming on or heading off.

*We made a deal for the old barn, the part that still stood at a kind of attention. Then we borrowed a huge trailer, and one of us went up into the loft and one stayed down below, and we went about the business of redeeming upwards of five hundred bales of an old farm’s old bounty, sailing each of them in a lazy arc down from the maw and setting them to right in the trailer as you’d set bricks in a wall, to make their way across the River of Abundance and Time and mulch there the worked over beds.

And each of those five hundred came with a handle of its own, a handle that had stood the test of maybe eighty years, stock still. It wasn’t the garish orange or blue plastic handle of those small bale fields that are left, if you can find one. No, each of them came with its own gleaming golden sisal handle, unfailing almost every one, holding, once more, so far from their jungle home.

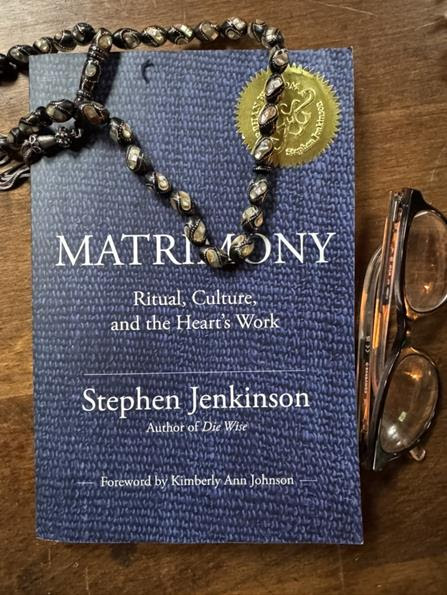

Stephen Jenkinson

Founder of Orphan Wisdom